Black Americans have largely positive views of medical researchers’ competence; majority concerned about the potential for misconduct

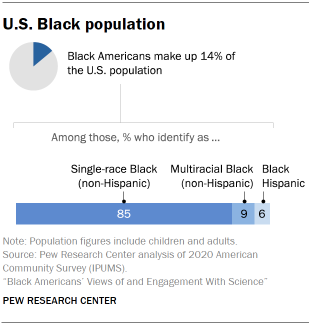

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand Black Americans’ perspectives of and experiences with science. We surveyed U.S. adults from Nov. 30 to Dec. 12, 2021, including 3,546 Black adults (inclusive of those who identify as single-race, multiracial and Black Hispanic). A total of 14,497 U.S. adults completed the survey. Subsequent reports will look at Hispanic Americans’ views and those of the overall U.S. adult population.

The survey was conducted on Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) and included an oversample of Black and Hispanic adults from the Ipsos KnowledgePanel. Respondents on both panels are recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the survey questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

The Center also completed six focus groups with Black Americans from July 13-22, 2021. The focus groups were moderated by Lisa Gaines McDonald of Research Explorers, Inc. Each group discussion was held online for 90 minutes and included three to six men and women; there were a total of 28 participants. Each group was designed to include younger and older age groups, people with higher and lower levels of education, and those living in the metropolitan areas of Atlanta, GA; Chicago, IL; Charlotte, NC; and Houston, TX.

Here is the moderator guide used for the focus group discussions, and more on its methodology.

This study was informed by advice from a group of advisers with expertise related to Black and Hispanic attitudes and experiences in science, health, STEM education and other areas. Pew Research Center remains solely responsible for all aspects of the research, including any errors associated with its products and findings.

This report is made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which received support from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

Science offers the promise to aid society in tackling its most pressing problems, lifting living standards, health and life expectancies. Learning about science can enrich people’s lives in and outside of the classroom, and advances in scientific developments can spark amazement while transforming the ways we live and work.

A new Pew Research Center survey takes a wide-ranging look at Black Americans’ views and experiences with science, spanning medical and health care settings, educational settings, and as consumers of science-related news and information in daily life.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a prominent reminder of the disparate health impacts Black Americans face, and of long-standing concerns about levels of trust or mistrust between scientists and Black communities.

Against this backdrop, there are ongoing concerns that the segments of the public most engaged with science – people who attend science-related events, participate in medical research studies, and fill science, technology, engineering and math classrooms and the professional ranks of these fields – do not adequately reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of the nation.

The new survey, along with a series of focus groups, highlight the multifaceted views Black Americans hold when it comes to trust in medical research scientists. The findings speak to how contemporary experiences with the health care system, as well as past injustices, inform the range of attitudes Black adults express. In this and other topics addressed in the survey, there are important differences in how Black Americans see these issues depending on their education, age, gender and other characteristics.

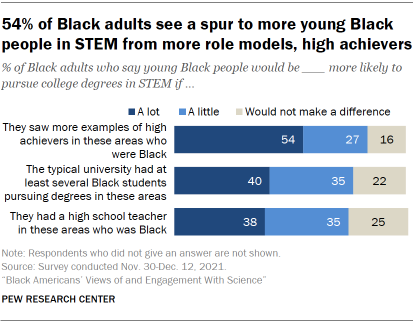

The importance of representation for Black Americans is a through-line seen across the topics covered in the survey. A majority of Black Americans say more examples of Black high achievers in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) would encourage more young Black people to pursue training in these fields. And issues around representation are at the center of doubts some focus group participants expressed about the openness of science-related professions to Black people.

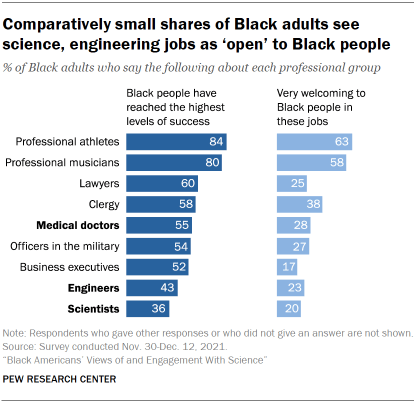

Among the most telling findings are the limits Black adults perceive regarding the openness of scientists, engineers and medical doctors to Black people in these professions.

Relatively few Black adults believe that Black people have reached the highest levels of success as scientists (36%) or engineers (43%); a 55% majority say Black people have reached this level of success as medical doctors.

By contrast, large majorities of Black adults say Black people have reached the highest levels of success as professional athletes (84%) and musicians (80%). Six-in-ten say they have done this as lawyers and 58% say they have done this in the clergy.

Asked more directly to evaluate how welcoming these groups are to Black people in these jobs, just 20% of Black Americans say that scientists as a professional group are very welcoming of Black people. About four-in-ten (42%) say they are somewhat welcoming while 36% of Black Americans view scientists as not too or not at all welcoming to Black people in these jobs.

Perceptions of engineers are quite similar, with 23% saying this group is very welcoming to Black people in these jobs. Medical doctors fare only slightly better; 28% see them as very welcoming to Black people in their field.

STEM professions are not alone in this sense of being seen as no more than “somewhat” welcoming to Black professionals. Still, scientists and engineers received among the lowest ratings for openness to Black people across the nine professional groups included in the survey.

The survey findings also call attention to how visible Black achievement in STEM professional roles could potentially attract more young Black people to training programs in these fields.

A 54% majority says young Black people would be a lot more likely to pursue college degrees in STEM if there were more examples of high achievers in these areas who were Black; another 27% say this would help a little.

Black adults with a postgraduate (75%) or a college degree (73%) are especially likely to think that more examples of Black achievement in STEM would make young Black people a lot more likely to pursue degrees in these fields.

Smaller shares see other potential factors considered in the survey as critical. Although, majorities of Black Americans say that having a cohort of Black students pursuing degrees in these subjects at the typical university would help at least a little to attract more young Black people to these programs. A similar share say the same about having a Black high school teacher in STEM subjects. Views on this factor were about the same among the roughly half of Black Americans who report having this experience and the half who did not.

Analysis of the survey focuses on Black Americans, including those who identify as single-race Black, multiracial Black, and Black Hispanic.1

The survey was conducted Nov. 30 to Dec. 12, 2021, and included 3,546 Black adults; findings based on all Black adults surveyed have a margin of error of plus or minus 2.8 percentage points.

Previous Center findings highlight instances where views about science and scientists among Black adults are less positive than those of other racial and ethnic groups. A separate survey conducted in November 2021 finds about half of Black Americans (52%) say that science has had a mostly positive effect on society, compared with greater shares among White (68%) and Hispanic (62%) Americans. Among Black adults, 43% say that science has had an equal mix of positive and negative effects, and just 5% say the effect of science has been mostly negative.

This study aimed to better understand such differences. The survey casts a wide net across the key ways in which people experience and connect with science. The approach was informed by a panel of advisers with expertise on Black and Hispanic views and experiences in American society broadly, and in connection with science, health and STEM education.

The questions asked in the survey were also informed by a set of six focus groups conducted virtually in July 2021 among Black adults that elicited views about the COVID-19 pandemic and experiences and beliefs about the health and medical care systems, as well as people’s interests in science topics and their past experiences with STEM schooling.

Subsequent reports will provide an in-depth look at the views and experiences of Hispanic Americans and a broader look at public opinion among the general U.S. population.

Many Black Americans express trust in scientists and medical scientists; majorities also see potential for research misconduct, have concerns about researcher accountability

Most Black adults say they have either a great deal (28%) or a fair amount (50%) of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public’s best interests. About two-in-ten (21%) say they have not too much or no confidence in medical scientists.

Black Americans’ trust in medical scientists, as well as that for scientists, fell over the past year, as it also did among the general public. Even so, Black Americans’ trust in medical scientists is greater than that for other major groups and institutions including the military, K-12 public school principals and religious leaders.

As people think about different facets of trustworthiness, a majority of Black Americans lean toward trusting medical researchers’ competence, their care for the public’s interests, and the information they provide about their research. A third of Black Americans say that medical researchers do a good job all or most of the time and another 46% say this occurs some of the time. Roughly two-in-ten (18%) say this happens only a little or none of the time.

At the same time, notable shares of Black adults express doubt about how often medical researchers admit and take responsibility for their mistakes. Just one-in-ten Black adults say that medical research scientists do this all or most of the time; 47% say this occurs at least some of the time. Half say this happens only a little or none of the time. Over the last few years, Black adults have become less confident that medical researchers admit mistakes and take responsibility for them; the share who say this happens at least some of the time is down 19 points since 2019.2

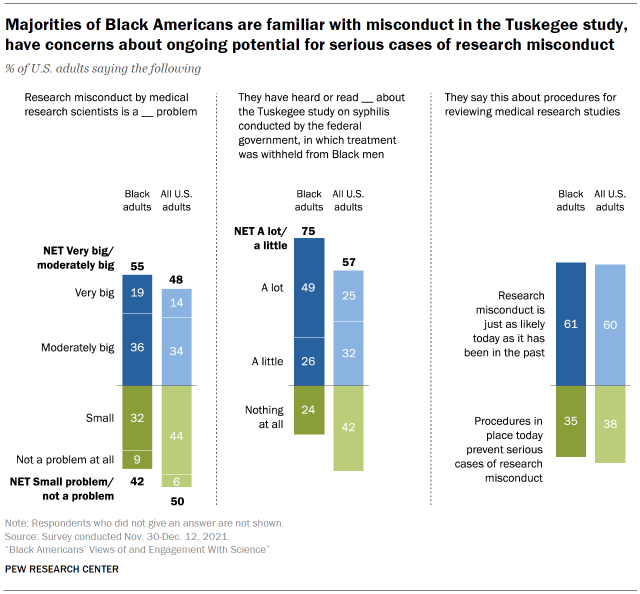

In the new Center survey, 55% of Black adults describe misconduct by medical research scientists as a moderate or very big problem – a share that continues to be a bit higher than that of U.S. adults overall.

The legacy of egregious medical misconduct in the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, commonly known as the Tuskegee syphilis study, continues to resonate widely among Black Americans. Three-quarters of Black Americans say they have heard a lot (49%) or a little (26%) about the federal government’s study on syphilis, which withheld treatment from Black men, leading to preventable deaths and a worsening of symptoms among those study participants.

Older Black adults have the highest level of familiarity the Tuskegee syphilis study, but a majority of those under age 30 say they know at least a little about the study.

Awareness of the Tuskegee study is far lower among U.S. adults overall: A quarter say they know a lot about the study, while another 32% say they know at least a little about this study.

Black Americans have a cautious outlook toward medical research going forward. About six-in-ten (61%) believe that serious cases of misconduct in medical research are just as likely today as they have been in the past. A smaller share (35%) says there are procedures in place today to prevent serious cases of research misconduct. Black Americans’ views on these issues are virtually identical to those of the general population.

The Center survey was conducted more than two years into a pandemic which had disproportionate health effects on Black Americans. As stark evidence, the most recent estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau projects life expectancy at 71.8 years for Black Americans, the lowest since 2000 and below the estimates for other racial and ethnic groups.

When asked to consider potential factors responsible for differences in health outcomes for Black people, 63% of Black adults view less access to quality medical care in the area they live to be a major reason why Black people in the U.S. generally have worse health outcomes than other adults.

Majorities also view a range of other factors as playing at least a minor role, including more environmental problems in communities where Black people live, a greater likelihood of preexisting health conditions among Black people, and health care providers being less likely to give Black people the most advanced care.

In their own clinical care experiences, 61% of Black adults give their health care provider positive marks – either excellent or very good – for the care they’ve received most recently.

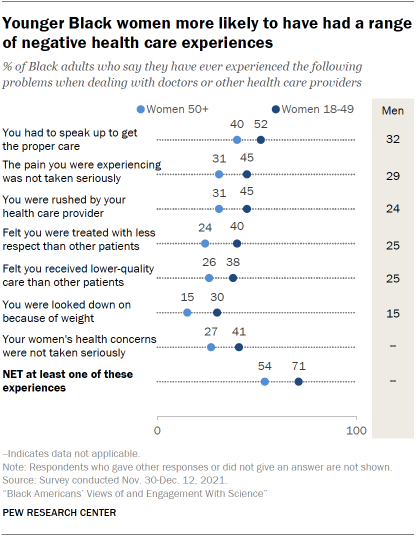

Still, 55% of Black adults say they’ve had at least one of several negative experiences with health care providers in the past, such as feeling they had to speak up to get the proper care or that the pain they were experiencing was not being taken seriously.

In this regard, Black Americans’ experiences with medical care are similar to those of all U.S. adults, 58% of whom say they have had at least one of these negative experiences with health care providers in the past.

The views and experiences of younger Black women, ages 18 to 49, stand out in a number of ways. This group is particularly likely to report having at least one of seven kinds of negative experiences with routine health care in the past (71% say this).

They are also more likely than other Black adults to say they would prefer to see a Black health care provider for routine care: 45% say this, while 50% say it makes no difference to them.

And larger shares of younger Black women say that Black health care providers are generally better than others at looking out for their best interests (41%), taking their symptoms seriously (40%) and treating them with respect (39%).

Majorities of older Black women and Black men across age groups say it makes no difference whether they see a Black doctor for routine care. No more than three-in-ten in each of these groups consider Black health care providers better than other providers at looking out for their interests, taking their symptoms seriously or treating them with respect. Majorities view Black healthcare professionals as about the same as others at providing key aspects of medical care.

The coronavirus outbreak and COVID-19 vaccine news has engaged many Black adults; a majority saw or heard about events related to the outbreak in their local area

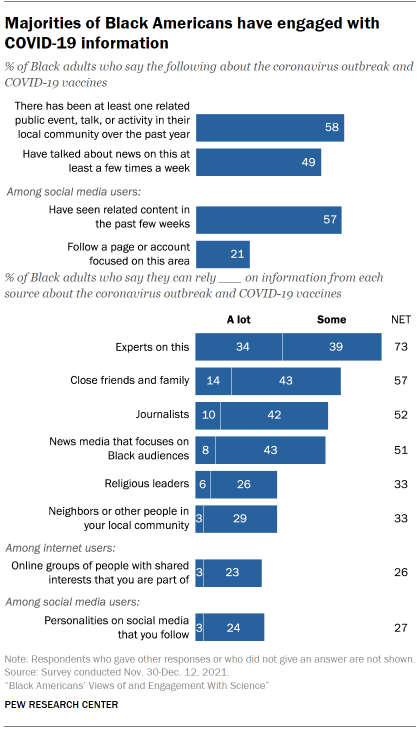

Amid the coronavirus pandemic and concerns about the omicron variant, a majority of Black Americans (58%) said in December 2021 that they heard about at least one public event or activity related to the outbreak or COVID-19 vaccines in their local community. Roughly half (49%) said they talked about related news at least a few times a week. Among those on social media, 57% said they had seen coronavirus-related content in the past few weeks.

The findings suggest a relatively engaged Black American public. Figures among all U.S. adults are roughly similar, although an even larger share of all U.S. adults on social media said they had seen coronavirus-related content in the past few weeks (68% compared with 57% of Black social media users).

About seven-in-ten Black Americans say they can rely on information from experts on the coronavirus outbreak and vaccines either a lot (34%) or some (39%).

A majority (57%) also say they can rely on information from close family and friends about this at least some. About half of Black adults say this about information from journalists (52%) or news media that focus on Black audiences (51%).

Fewer say they can rely at least some on information about the coronavirus from other groups. Among Black internet users, roughly a quarter say they can rely at least some on information related to the outbreak and COVID-19 vaccines from online groups with shared interests that they are part of, and just 3% say they can rely on information from such groups a lot.

Black adults’ recollections of their own experiences in STEM education present a mixed picture of encouragement and acceptance, especially for those in STEM jobs today

Black adults remain underrepresented in the STEM workforce, with little sign that the educational pipeline will offer near-term improvements.

The survey asked those with a high school diploma or more education to consider their most recent experiences with classwork in a science, technology, engineering or math subject as one way to gauge the degree to which people encounter potential encouragements or discouragements in the educational system. Across the set of six questions, larger shares of Black Americans recalled at least one of three positive experiences than any of three negative ones.

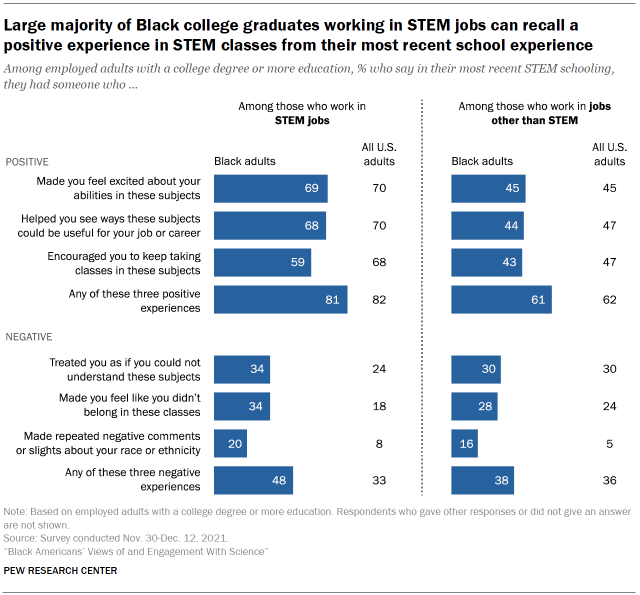

Looking at Black adults working in STEM jobs today with a college or postgraduate degree – a group that is more likely to have taken high-level classes in STEM – 81% say they recall at least one of three positive experiences in their classes. About seven-in-ten (69%) say someone made them feel excited about their abilities in these areas, 68% say someone helped them see ways that these subjects could be useful in their job or career and 59% say someone specifically encouraged them to keep taking classes in these subjects.

A smaller majority of Black college graduates working in non-STEM jobs (61%) recall at least one of these three positive experiences.

Among all U.S. adults with a college degree or more education, those working in STEM jobs are about equally likely to say they have had at least one of these three positive experiences. This group is somewhat more likely to say that someone encouraged them to keep taking STEM classes, however (68% vs. 59% among Black college graduates working in STEM).

Black college graduates working in STEM are more likely than all STEM workers – regardless of their racial or ethnic background – to recall some kind of mistreatment in their most recent STEM schooling (48% vs. 33%). Roughly a third of Black college graduates in a STEM job say that someone treated them as if they could not understand these subjects or made them feel as if they didn’t belong in these classes (34% each). Two-in-ten say that someone made repeated negative comments or slights about their race or ethnicity. The survey cannot speak to whether such experiences originated from interactions with teachers, counselors, students or other contextual aspects of these experiences.

These findings are in line with a 2017 Center survey which found 62% of Black STEM workers saying they had experienced at least one of eight forms of racial or ethnic discrimination in the workplace. This was greater than the shares of Black workers in non-STEM jobs (50%) and greater than the shares of Asian (44%), Hispanic (42%) and White STEM workers (13%) who said the same.

CORRECTION (Jan. 12, 2024): Chapter 3 of a previous version of this report included an incorrect percentage because one survey question was asked only of women. Among Black adults, 55% say they have ever had at least one of six negative experiences with doctors or other health care providers.